Richard Harris Denton

Was born at 61 Burgate, Canterbury on 6th December 1788 and educated at St Paul's School and Oxford.

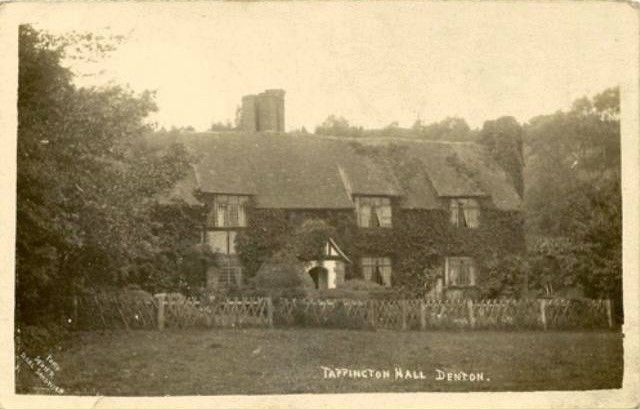

His father, dying in 1795, bequeathed a moderate estate to his only son, then about five or six years of age. A portion of this property consisted of the manor known as Tappington (generally pronounced Tapton) Wood, so often alluded to in The Ingoldsby Legends.

At nine he was sent to St. Paul's school, but his studies were interrupted by an accident which shattered his arm and partially crippled it for life. Thus deprived of the power of bodily activity, he became a great reader and diligent student.

In 1807 he entered Brasenose College, Oxford, intending at first to study for the profession of the law. Circumstances, however, induced him to change his mind and to enter the church.

In 1813 he was ordained and took a country curacy. He married Caroline, daughter of Captain Smart of the Royal Engineers in 1814.

He became the Vicar of Warehorne and Snargate in about 1818 and rose to became a minor cannon of the Chapel Royal at St Pauls in 1824.

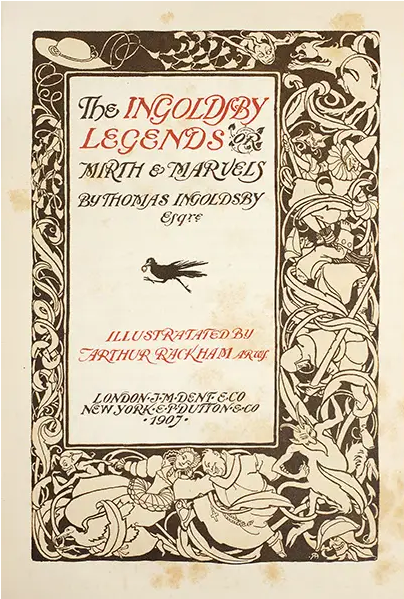

In 1826 he first contributed to Blackwood's Magazine; and on the establishment of Bentley's Miscellany in 1837 he began to furnish the series of grotesque metrical tales known as The Ingoldsby Legends.

It was Mr Barham's happiness to form an intimate friendship with the Hughes family. His duties at St. Paul's were the means of bringing him under the frequent observation of Dr. Hughes, who was resident canon of the cathedral. To Mrs. Hughes, more especially, the correspondent of Sir Walter Scott, Southey, and others of the age, Barham was indebted, not only for a large proportion of the legendary lore which forms the groundwork of the Ingoldsby writings. Inscribed in a copy of The Ingoldsby Legends, presented to the lady in question, implies no more than the actual fact

'To Mrs. Hughes who made me do 'em,

Quod placeo est -- si placeo -- tuum.'

In politics he was a Tory of the old school; yet he was the lifelong friend of the liberal Sydney Smith, whom in many respects he singularly resembled. Theodore Hook was one of his most intimate friends.

The Ingoldsby Legends were first published in book form in 1840. These became very popular, were published in a collected form and have since passed through numerous editions.

Also 1840, Barham succeeded, in course of rotation, to the presidency of Sion College; and in 1842, his long services at St. Paul's were rewarded with the divinity readership in that Cathedral, and by his being permitted to exchange his living for the more valuable one of St. Faith, the duties of which were far less onerous than those he had fulfilled during well-nigh twenty years. He still continued under the bishop's licence in his old abode in Amen Corner. This, indeed, he was enabled to do till his death, although shortly after his induction, the death of Sidney Smith placed the house in other hands.

His life was grave, dignified and highly honoured. His sound judgment and his kind heart made him the trusted councillor, the valued friend and the frequent peacemaker; and he was intolerant of all that was mean and base and false.

The first indications of Barham's fatal disease exhibited themselves on the day of the Queen's visit to the City - October 28, 1844 - for the purpose of opening the Royal Exchange. He had accompanied his wife and daughters to a friend's house to witness the procession, and had even remarked, as a cutting east wind whistled through the open windows, that, in all probability, that day's sight-seeing would cost many of the imprudent gazers their lives. In the course of the evening he was attacked with a violent fit of coughing and severe inflammation in the throat. It was found in the following June that recovery was impossible.

To say that be received the intimation with fortitude, would afford a very inadequate notion of the calmness and contentment with which he regarded his approaching end. Having arranged all the details of his affairs, he took holy communion for the last time, in company with all his household, and set himself, in perfect self-possession, the final preparation for his passing.

His last writings, entitled As I laye a-thynkynge, were written but a few days before his death and were placed, at his express desire, for publication. On the morning of June 17, 1845, he expired, without a struggle, in faith, and hope, and in charity with all men.

Independent of any admiration that Barham's wit and talent might excite, there was a warm heart about him, which rendered him justly dear to many. His spirits were fresh and buoyant, his constitution vigorous, and his temperament sanguine. His humour never ranged 'beyond the limits of becoming mirth,' and was in its essence free from gall. Where irony was his object, it was commonly just, and always gentle. On his writings might, in fairness, be inscribed:--

'Non ego mordaci distrinxi carmine quenquam,

Nulla venenato est litera mixta joco.'